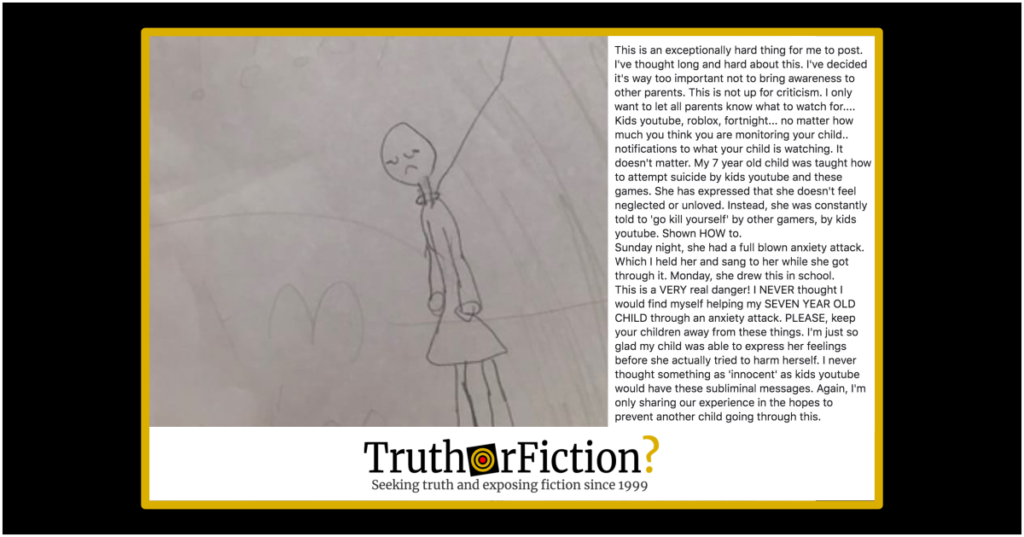

On February 12 2019, Facebook user Meridy Leeper shared an image purportedly of a drawing by her young child and the following message about suicidal ideation in small children apparently prompted by videos beneath parental radar on YouTube, TikTok, Roblox, and Fortnite — among other platforms:

This is an exceptionally hard thing for me to post. I’ve thought long and hard about this. I’ve decided it’s way too important not to bring awareness to other parents. This is not up for criticism. I only want to let all parents know what to watch for….

Kids youtube, roblox, fortnight… no matter how much you think you are monitoring your child.. notifications to what your child is watching. It doesn’t matter. My 7 year old child was taught how to attempt suicide by kids youtube and these games. She has expressed that she doesn’t feel neglected or unloved. Instead, she was constantly told to ‘go kill yourself’ by other gamers, by kids youtube. Shown HOW to.

Sunday night, she had a full blown anxiety attack. Which I held her and sang to her while she got through it. Monday, she drew this in school.

This is a VERY real danger! I NEVER thought I would find myself helping my SEVEN YEAR OLD CHILD through an anxiety attack. PLEASE, keep your children away from these things. I’m just so glad my child was able to express her feelings before she actually tried to harm herself. I never thought something as ‘innocent’ as kids youtube would have these subliminal messages. Again, I’m only sharing our experience in the hopes to prevent another child going through this.

This claim appeared to be more than the usual social media panics. In March 2017, TheOutline.com was among news sites covering sinister and alarming videos embedded in content played for preschool children. In that report, the writer described coming across what she described as “off brand” Peppa Pig clips on YouTube:

The video, titled “#Peppa #Pig #Dentist #Kids #Animation #Fantasy,” is completely horrifying. Though the animation sort of looks like an actual episode of Peppa Pig, it’s poorly done, and the narrative quickly veers into upsetting territory. Peppa goes to the dentist, who has a giant needle and a lot of scary tools. The pigs are mysteriously forest green rather than pink. Burglars appear to try to burgle.

Peppa Pig is a show for preschoolers. Knock-off Peppa Pig is the stuff of nightmares.

Later that month, BBC also covered a spate of videos that appeared to be for young children, but that harbored disturbing or frightening scenes packaged as wholesome content:

Hundreds of these videos exist on YouTube, and some generate millions of views. One channel “Toys and Funny Kids Surprise Eggs” is one of the top 100 most watched YouTube accounts in the world – its videos have more than 5 billion views.

Its landing page features a photo of a cute toddler alongside official-looking pictures of Peppa Pig, Thomas the Tank Engine, the Cookie Monster, Mickey and Minnie Mouse and Elsa from Frozen.

But the videos on the channel have titles like “FROZEN ELSA HUGE SNOT”, “NAKED HULK LOSES HIS PANTS” and “BLOODY ELSA: Frozen Elsa’s Arm is Broken by Spiderman”. They feature animated violence and graphic toilet humour.

In June 2018, the Guardian revisited the issue and widespread discussion of its effects on forums for parents:

Parents reported that their children were encountering knock-off editions of their favourite cartoon characters in situations of violence and death: Peppa Pig drinking bleach, or Mickey Mouse being run over by a car. A brief Google of some of the terms mentioned in the article brought up not only many more accounts of inappropriate content, in Facebook posts, newsgroup threads, and other newspapers, but also disturbing accounts of their effects. Previously happy and well-adjusted children became frightened of the dark, prone to fits of crying, or displayed violent behaviour and talked about self-harm – all classic symptoms of abuse. But despite these reports, YouTube and its parent company, Google, had done little to address them. Moreover, there seemed to be little understanding of where these videos were coming from, how they were produced – or even why they existed in the first place.

[…]

For adults, it’s the sheer weirdness of many of the videos that seems almost more disturbing than their violence. This is the part that’s harder to explain – and harder for people to understand – if you don’t immerse yourself in the videos, which I’d hardly recommend. Beyond the simple knock-offs and the provocations exists an entire class of nonsensical, algorithm-generated content; millions and millions of videos that serve merely to attract views and produce income, cobbled together from nursery rhymes, toy reviews, and cultural misunderstandings. Some seem to be the product of random title generators, others – so many others – involve real humans, including young children, distributed across the globe, acting out endlessly the insane demands of YouTube’s recommendation algorithms, even if it makes no sense, even if you have to debase yourself utterly to do it.

The Guardian cited a 2017 New York Times investigation of the “dark corners” of content platforms for preschool and grade school children, which, like other accounts, began with a parent’s unexpected brush with violent and suggestive content:

It was a typical night in Staci Burns’s house outside Fort Wayne, Ind. She was cooking dinner while her 3-year-old son, Isaac, watched videos on the YouTube Kids app on an iPad. Suddenly he cried out, “Mommy, the monster scares me!”

When Ms. Burns walked over, Isaac was watching a video featuring crude renderings of the characters from “PAW Patrol,” a Nickelodeon show that is popular among preschoolers, screaming in a car. The vehicle hurtled into a light pole and burst into flames.

The 10-minute clip, “PAW Patrol Babies Pretend to Die Suicide by Annabelle Hypnotized,” was a nightmarish imitation of an animated series in which a boy and a pack of rescue dogs protect their community from troubles like runaway kittens and rock slides. In the video Isaac watched, some characters died and one walked off a roof after being hypnotized by a likeness of a doll possessed by a demon.

[…]

While the offending videos are a tiny fraction of YouTube Kids’ universe, they are another example of the potential for abuse on digital media platforms that rely on computer algorithms, rather than humans, to police the content that appears in front of people — in this case, very young people.

As of late February 2019, that exact video is still up and appears to have been untouched by YouTube moderators. It can be viewed here.

Amidst ongoing parental concern over “dark” and “violent” preschool videos, another rumor spread: that these videos are sparking violent or suicidal behavior in young people. It is similar to a 2016 rumor about Internet interest in the purported “Blue Whale” suicide game; that appeared to mostly involve teenagers, but those stories have unsettling commonalities involving violent ideation and suicide contagion.

While individual anecdotes about their effects (such as the Facebook post quoted above) are not verifiable beyond doubt without more data, the existence of the described content is certainly documented, and it does not seem like a stretch to assume that children are imitating the behavior they see displayed by familiar, trusted characters. Platforms such as childrens’ YouTube, TikTok, Roblox, and Fortnite channels are aware that the videos appear, but they do not seem to have made any effort to stop those same videos from spreading. The claim is true — videos with sinister and suggestive content masquerading as popular preschool videos (like Peppa Pig and Paw Patrol) remain on children’s content streaming platforms.